In 2019, back when my hair was longer and I was arguably a “lesser” version of myself, I walked into my local shop. I was in the middle of a crisis, the kind of mental fog that makes the world feel sharp and abrasive.

She was there, restocking shelves. We started talking. I don’t remember how it started, but within minutes, I found myself blurting out my problems to this stranger. She didn’t back away. She didn’t give me the polite “customer service nod” and edge toward the stockroom. She listened.

Over the next few years, our conversations stayed on the surface. We talked about the weather, the news, and the mundanity of life. But underneath that surface, something shifted in 2023.

I started learning about her—her hobbies, her travel plans, the way she saw the world. The more I saw her, the more everything she said became etched into my mind. Birthdays. Interests. The specific cadence of her voice.

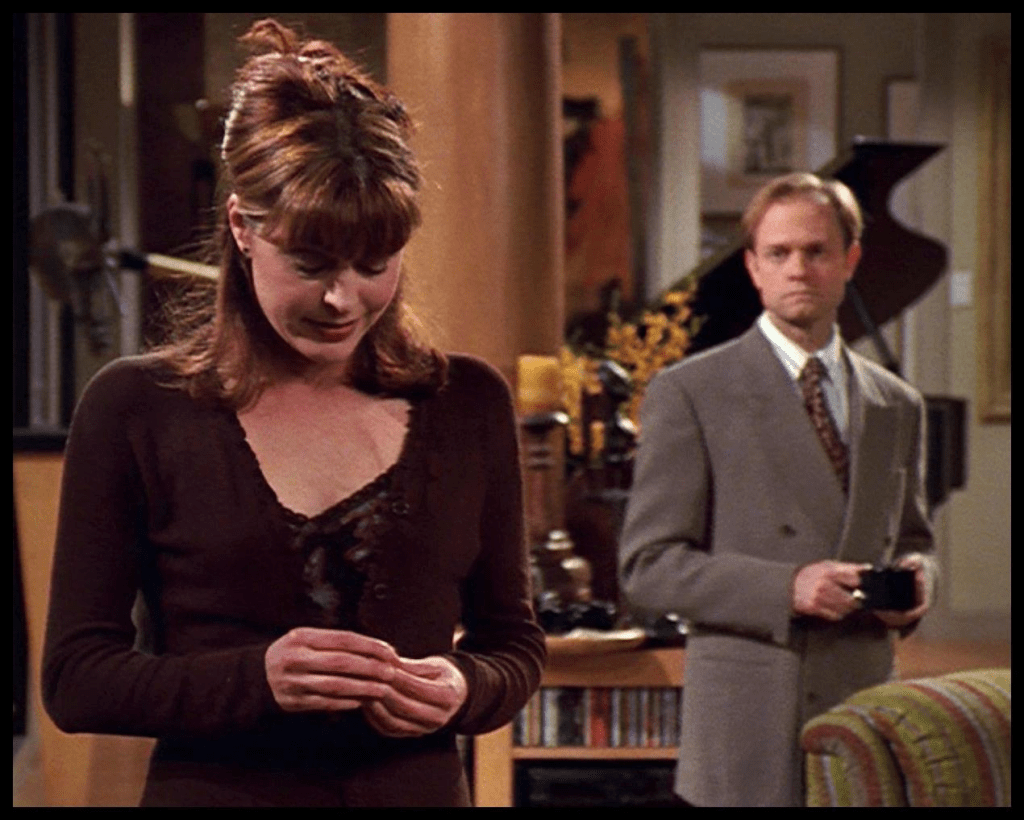

It was a “Niles and Daphne” situation. It was terrifying and electric. I would walk into the shop, and my eyes would immediately scan for her. If she wasn’t there, the room felt empty. If she were, the room felt like it was vibrating.

But I never said anything.

I had made a decision, you see. A “logical” decision based on the debris of my health battles. I convinced myself that a relationship was impossible. I told myself, “I am a stroke survivor. I have baggage. I am a burden.”

And because I believed I was a burden, I decided to carry the weight of those feelings alone rather than risk sharing them.

The Burden Paradox

If you read Mark Manson, you know we are excellent at creating narratives that protect our egos while simultaneously ruining our lives.

My narrative was The Burden.

After the stroke, it is easy to view yourself as a net negative in someone else’s life. You think about the appointments, the fatigue, the limitations. You run the calculus and think, “Why would she want this? She deserves someone whole.”

This is a lie. It is a defence mechanism designed to keep you safe from rejection. If you disqualify yourself before the race starts, you never have to worry about losing. But you also never get to run.

I spent years talking to her, letting her into my life in inches, while she did the same. She treated me not as a patient, not as a “survivor,” but as a human being. She read my writing. She supported me when my health took a nosedive.

In my head, I was planning a future. I wanted to take her to London to see her favourite musical. I had an invitation to be shown around the city by her, a perfect setup. It was right there. The script was written.

But then came the “Wait But Why” moment – the procrastination monkey.

- “I can’t go yet, I have financial issues.”

- “I’m waiting on this job opportunity to clear up.”

- “I’ll save a little more, then I’ll ask.”

I was waiting for the perfect time. I was waiting for the stars to align so that I wouldn’t have to feel vulnerable.

The Punch to the Heart

The universe does not care about your timeline. While I was busy saving money and waiting for the “perfect moment,” life happened.

She announced she was moving on to another job.

It felt like a physical punch to the heart. The window I had been staring at for years, terrified to open, was suddenly bricked over.

On her last day, I gave her a card and chocolates. This was it. This was the moment to say, “You mean everything to me. You made me feel human when I felt like a medical statistic. Let’s go to London.”

Instead, I wrote:

“You are a super trouper. I’ll miss you.”

“Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.” — Maya Angelou.

That’s it.

A generic-ish compliment from Abba and a quote about self-improvement.

It is one of the great regrets of my life. It pained me to write it because it was so painfully safe. I hid behind Maya Angelou because I was too afraid to stand in front of Hannah.

The Noise and the Signal

I recently watched a clip from Elementary that hit me harder than I expected. Sherlock Holmes, an addict in recovery, is speaking to a group:

“My senses are unusually—well, one could even say unnaturally—keen. And ours is an era of distraction. It’s, uh, a punishing drumbeat of constant input. This cacophony, which follows us into our homes and into our beds and seeps into our souls… So in my less productive moments, I’m given to wonder if I’d just been born when it was a little quieter out there, would I have even become an addict in the first place? Might I have been more focused? A more fully realised person?”

I feel that. The punishing drumbeat of constant input. The social interaction with others and the anxiety it brings. The appointments. The financial stress. The health anxiety. The noise of “The Long Road Ahead.”

Last month, she was back at my local shop, visiting. I normally would be there. But I wasn’t. I was at a medical appointment—an appointment that, ironically, turned out to be a complete waste of time.

I stopped into the shop later, driven purely by hunger, only to be told I had missed her by minutes. The hunger vanished. The frustration with the appointment vanished. All that was left was the hollow ringing of bad timing. The noise of my life had once again drowned out the signal.

The Dictionary of Sorrows

For my birthday, a friend gave me The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows. It’s a beautiful book that invents words for emotions we all feel but can’t articulate.

It got me thinking about connection. Connection has always been hard for me, rooted in childhood issues and that nagging fear of being “too much” for people. But while reading that book, I came across a quote by Louise Erdrich that stopped me cold.

If you take nothing else from this blog post, please take this:

“Life will break you. Nobody can protect you from that, and living alone won’t either, for solitude will also break you with its yearning. You have to love. You have to feel. It is the reason you are here on earth. You are here to risk your heart. You are here to be swallowed up. And when it happens that you are broken, or betrayed, or left, or hurt, or death brushes near, let yourself sit by an apple tree and listen to the apples falling all around you in heaps, wasting their sweetness. Tell yourself you tasted as many as you could.”

I have spent so much time trying to avoid being broken that I have broken myself through solitude. I was so afraid the apples would be sour that I let them all fall to the ground and rot.

A Note on Regret (The James Clear View)

Research on regret is clear on one thing: In the long run, we regret inaction more than action.

We regret that we didn’t send more than the one that got a bad reply. We regret the trip we didn’t take, more than the one where it rained every day. We regret the “I love you” we choked back more than the one that wasn’t reciprocated.

Why? Because when you act and fail, the story ends. You grieve, you learn, you move on. When you don’t act, the story never ends. It plays on a loop in the back of your mind. It becomes a phantom limb—it’s not there, but it still hurts.

I tried to protect myself from the pain of rejection. I told myself I was saving her from the “burden” of me. But all I did was make sure neither of us saw what could happen.

My advice to you and me

Here is my advice to you, the reader. If you are waiting – stop. If you think you are a burden, you are not. If you are waiting for the noise to stop so you can hear the music, it won’t. You have to sing over it.

Risk your heart. Be swallowed up. Taste the apples.

And finally…

Hannah, if you are reading this:

I should have written more than a quote in that card. I should have told you that you are unlike anyone I’ve met. I should have said that you are far more interesting than the world gives you credit for. I should have told you about London.

I missed you at the shop last month because I was busy dealing with the “noise,” but I don’t want to miss the signal anymore.

If you feel like you’d like to pursue this—the London trip, the conversation, the “us”, then please email me. I’d like to tell you this in person.

Leave a comment